A Rich Harmony

Campus diversity empowers many voices

Jennifer Taylor conducted groundbreaking research on crabs' skeletal growth with support from the Sequoyah Dissertation Fellowship.

Jennifer Taylor, a Cherokee Indian, remembers growing up poor in San Fernando Valley, Calif. Along with five other children, she was raised by a single mom. The children were expected to find jobs the minute they graduated high school so they could help out, and like previous generations of Taylors, most of them did. But Jennifer chose a different path, becoming the first among her family to enter a university and emerge with a graduate degree.

Taylor earned a doctoral degree in Biology from UNC-CH. As a recipient of the Sequoyah Dissertation Fellowship in the Royster Society of Fellows — an interdisciplinary fellowship program that assists some of Carolina’s most-accomplished doctoral students to complete their dissertations — Taylor is also among the ranks of graduate students who have made significant contributions to science through groundbreaking research.

At Carolina, Taylor studied how crabs support themselves when they lose their skeletons to grow, which crustaceans do repeatedly in their lifetimes. She found that crabs temporarily adopt a liquidbased skeleton similar to that of worms while they molt. Her work was the first description of an animal that alternates between two types of skeletons and provides novel insights into the evolution and function of skeletal support systems.

The New York Times, National Geographic, and the journals Science and Nature all published the results of Taylor’s study. “It’s very rare for a student to catch the attention of any of these publications, which look for work that’s exceptionally relevant and impressive,” says Dean Linda Dykstra. “Jennifer published in all of them, which is nothing short of amazing.”

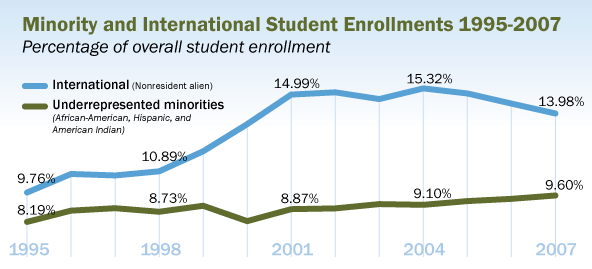

The presence of students like Taylor has helped foster a rich, multi-cultural and diverse learning environment. The Chancellor’s Task Force on Diversity acknowledges that UNC-CH works hard to recruit and retain quality minority students like her. Its 2005 report states that “education takes place most productively among persons with differing social backgrounds, economic circumstances, personal characteristics, philosophical outlooks, life experiences, perspectives, beliefs, expectations and aspirations …” Today, about 10 percent of Carolina’s graduate students belong to underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, and an additional 14 percent are international students.

To nurture minority students’ success, the Graduate School offers many types of support, from helping to arrange campus visits and orientation programs, to providing opportunities to dialog on race and culture, to offering fellowship and funding opportunities. Taylor received the Sequoyah Fellowship, a dissertation fellowship for American Indian graduate students conducting research on any topic or any graduate student conducting research on an American Indian topic.

Despite her outstanding research results, Taylor initially felt uncomfortable talking about her accomplishments. But professors and supervisors continued to push her. “I finally understood that staying quiet about things I do is a disservice to people who might be able to learn from me,” she says. “My experience at UNC opened me up. I talked to people and gave presentations all the time and I learned tremendously from the process.”

Taylor also evolved into a leader at Carolina, becoming heavily involved with the American Indian community both as president of the First Nation’s Graduate Circle, an American Indian graduate organization, and head organizer of the American Indian Graduate School Recruitment Week in 2006. By giving her time to these efforts, she helped further increase the rich diversity at UNC-CH.

Last summer, Taylor won a highly competitive postdoctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation and chose to work with faculty at the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of California at Berkeley. She hopes that her success as a biologist will inspire more minority students to pursue higher education.

“I really wish there were more of us going to university and getting a graduate education,” Taylor says. “I think it’s important to keep encouraging more American Indians and other unrepresented groups to take part in the academic community, because we have a lot to learn from it, and much to contribute as well.” • Margarita De Pano