Seeing the Elephant for All Its Parts

Interdepartmental Osmosis

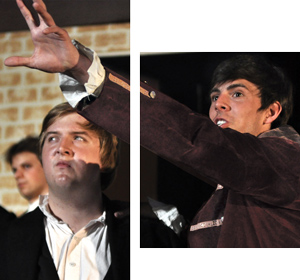

Searching for Spinoza embodies interdisciplinary scholarship

In an ancient tale, several blind men touch an elephant. One grabs the trunk. Another strokes a tusk. A third feels an ear. Subsequently, each man disagrees about what an elephant is.

The story teaches that avoiding misinterpretations and gaining complete answers requires the collaboration of critical minds. Questions must be tackled from multiple perspectives.

For this reason, UNC-Chapel Hill embraces interdisciplinary scholarship to combine a variety of academic disciplines, share ideas and resources, and produce new knowledge. Some are classic partnerships, others more creative. The collaboration between departments is part of the reason that Carolina is one of the best public universities in the country.

Interdisciplinary scholarship, for example, allows two science programs to team up to make a breakthrough in medicine. Interdisciplinary research also inspires new questions that do not have definitive answers. Yet.

Knocking Down Walls

In the compartmentalized world of academia, walls often separate departments. But the only walls in the Genetic Medicine Building where Terry Magnuson works hold up the building.

“The unique thing at Carolina is a culture that promotes collaboration and interaction across all boundaries,” says Magnuson, who serves as the Director and Chair of the Genetics Department. “The Carolina culture is very special.”

The science departments at UNC-Chapel Hill depend on each other. Even though it is logical to share resources, Magnuson says, “Programs in other institutions tend to be more territorial than we are here.”

Acting as teammates, not opponents, benefits more than the budget. The University’s commitment to interdisciplinary research also exposes students to new ideas and approaches.

“Interdisciplinary sharing allows students to reach out and incorporate different techniques and get lots of input from many different kinds of faculty,” Magnuson says.

The Genetics Ph. D. program has an enrollment of about 85 students who work in nine departments and more than 45 laboratories spread between the School of Medicine and the College of Arts and Sciences. The research addresses problems in biology and biomedical science through classical genetics and modern molecular methods. Classical genetics aims to understand how inherited traits manifest themselves. Modern molecular methods focus on how differences in DNA are interpreted into the molecular machine that makes cells work.

The wide range of scholarship has produced students who have received awards, grants, and fellowships for work with a range of areas including breast cancer research and vascular biology among others.

The emphasis on interdisciplinary research did not develop accidentally. Carolina understands the advantages of collaboration. Even if there were unlimited budgets and space, the University would encourage these partnerships.

“It’s set by the leadership,” Magnuson says. “Chancellor Holden Thorp and the various deans really believe in this. They eliminate roadblocks to allow someone in the School of Medicine to work with somebody in Biology, for example.”

The highways of free exchange allow students to produce results that benefit the scientific community. In January 2010, Kyle Gaulton, a genetics doctoral student, was the lead author of a journal article published in Nature Genetics for work he did in collaboration with a biology lab. Gaulton worked with six co-authors at UNC-Chapel Hill to map areas of the genome that control which genes are “turned on” or “off.” These discoveries impact the understanding of which people are most susceptible to type 2 diabetes and other common illnesses.

“Two very different areas of research were brought together into one study,” says Bob Duronio, Director of the Curriculum in Genetics and Molecular Biology. “It went from looking at the whole population using human genetics to a specific molecular function. That’s what was novel about the study.”

“Both of those things aren’t often done in one laboratory,” Duronio adds. “It only happens because of interdisciplinary science.”

An Unlikely Mix

At first glance, music, religion, and economics have little in common. At Carolina, however, faculty members from these seemingly disparate disciplines have found a place to engage each other, share resources, and creatively contribute to broader public issues.

Baruch Spinoza, a 17th century Dutch philosopher, is the inspiration for this unique interdisciplinary endeavor called the Spinoza Project (SP). The SP kindles discussion about religious freedom and the concept of the separation of church and state. “This project epitomizes the importance of bringing together arts, humanities, and sciences,” says Terry Rhodes, Chair of the Music Department. “By opening the conversation on such a pressing theme, we can generate new scholarship.”

“The project really fits with the University’s mission,” adds Randall Styers, Religious Studies Professor and SP faculty partner. “Ultimately, we want to provide people with the knowledge and understanding necessary to contribute to an important debate.”

Despite having just started, the SP is stimulating debates on Carolina’s campus. The University now offers a course that uses Spinoza’s philosophy to address the issue of religious freedom in Western culture. The class focuses on Christianity, but two graduate teaching assistants who specialize in Jewish and Islamic studies stir the conversation.

“The teaching assistants share a real investment in teaching students how to communicate across religious differences,” Styers says. “Teaching this class allows their scholarship to come to fruition.”

“Religious Studies is inherently interdisciplinary,” says graduate student Joseph Gindi. “Interdisciplinary orientations have been essential in my own work, which combines ethnographic fieldwork with historical study and textual analysis. It has also been important in my teaching here at the university.”

In April, the project hosted several service-learning activities. The Ackland Art Museum featured a thematic exhibition about the philosopher. The UNC-Chapel Hill Opera presented 5 world-premiere performances of the chamber musical "Searching for Spinoza." Finally, a series of roundtable discussions targeted morality and the separation of church and state.

“Carolina conducts many interdisciplinary projects,” Rhodes says. “But SP goes beyond the classroom and creates long-term interaction about a pressing issue that speaks to many people and disciplines.”

Through sharing resources or tackling an issue from multiple perspectives, interdisciplinary scholarship at Carolina blurs the line between traditional academic disciplines. This approach provides students and faculty with an unprecedented opportunity to push the boundaries of discovery. Seeing the elephant for all its parts puts the University in a position to lead.

♦ Brian Conlin & Luca Semprini