Sleuthing in the Stacks

Archival Work at the Library of Congress

“Hey guys, we've got another 'Ballet?'”

While working in a library archive, you tend to form inside jokes about the works you organize. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Musicology graduate students Ryan Ebright, Catherine Hughes, and Chris Reali, recipients of James W. Pruett Summer Research Fellowships, did while working on the Morton Gould collection at the Library of Congress last summer.

The year 2010 marked the third summer that Musicology students from Carolina have processed collections at the Library, while also conducting independent research in Washington, D.C. Ebright, Hughes and Reali worked on the fascinating and mysterious collections of 20th-century American composers Roy Harris and Morton Gould.

Chris Reali explains, "Morton Gould was a composer with his own orchestra and radio show. He also served as the president of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) from 1986 to 1994. He straddled a fence between the pop world (radio broadcast, Broadway and jazz tunes), and serious contemporary music, but much to his dismay, never fit comfortably into either. He was an important mid-century composer because he composed music across genres. Making his work accessible to a wider audience may fill a void in the scholarship of American music."

A song by William Billings from the New England Psalm-Singer, published in 1770, with an engraving by Paul Revere.

UNC-Chapel Hill Music Professor Mark Katz first exposed graduate students to these amazing opportunities three years ago with a trip to the Library. Professor Katz likens archival work to a "treasure hunt, a process of continual discovery." In the boxes of Gould's work, "we found scripts of shows that had not been produced, as well as musical sketches for some of the pieces. If something didn't wind up in the finished product, it would be recycled for something else," adds Reali. "The puzzle is connecting unfinished pieces and determining if they belong to a finished piece."

Gould didn't make it easy to sort through his sketches. "He would use the word 'ballet' on everything. It became a joke with us because he literally had hundreds of sketchbooks with melodies that would just say 'Ballet?'" reminisces Hughes. Those mysteries are part of what makes processing a collection so captivating and creates such a unique opportunity for music students.

For the Library, musicology scholars contribute specialized knowledge. The Library has employees who can process the letters, correspondence and photographs. But as Ebright, Hughes and Reali sorted through the boxes of material, they analyzed melodies and matched sketches with musical works; this indispensable skill takes the archiving process to the next level.

This additional expertise also enables the Library to bring boxes out of storage more quickly. "The Roy Harris and Morton Gould collections sat there for almost 10 years before we worked on them," says Ebright. "We even received a thank you letter from Gould's daughter, a very rare event with archiving!" Reali exclaims.

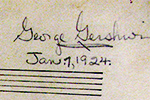

Just being in the Library was a thrill for the students. They had the privilege of seeing the originals of works such as George Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue" and Rodgers and Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things" from The Sound of Music. "Just seeing all the correspondence, written music, essays, pictures, photos—it was all incredible. You are holding history in your hands. Having access to the Library's other collections was spectacular," says Ebright. Hughes agrees: "It's amazing to see the originals. Walking through the stacks and seeing original Brahms, Mozart, Mendelssohn—you start to feel the drool coming out of your mouth."

That's part of what makes working in an archive an invaluable experience for any student. Reali feels this aspect of the work was one of the most profound. "It's one experience to walk through the front door of an archive, sit down at the desk, ask for materials and have them brought out to you. It's a whole different experience to go in the back door and have literally carte-blanche access to everything. We were privileged to see a portion of the jewels of the collection because we were employees."

Not only does the Library benefit from having musicology scholars process works, but the fellows also gain skills that augment what they learn on campus and which they can draw upon in the future. Understanding how works are processed and organized in an archive will undoubtedly help them in their own research. "You learn about how libraries are set up and what goes into organizing a collection. It's sort of a reversed way of thinking: what will researchers want from the collection and what can we do to make it easier? Flipping your thinking like that is really fascinating," says Hughes. Reali believes that the behind-the-scenes experience "helps you formulate questions. When I go back to another archive to conduct research, I'll know what to ask."

The fellows work not only in the Library of Congress, but are also given the opportunity to work on independent research projects. Reali studied a cappella sacred music recordings made by Robert Sonkin in Gee's Bend, Alabama in the 1940s. He conducted the bulk of this research across the street at the American Folklife Center, which houses these recordings. Hughes's independent research focused on the radio show of Walter Damrosch, who recorded a music education and appreciation program for children on NBC for 13 years. After reading transcripts of the shows here in Chapel Hill, she had the opportunity to hear recordings of the show in the Library's Performing Arts Reading Room. Ebright studied the Chamber Music Society of Baltimore, trying to uncover why it commissioned the works it did in the 1970s and 80s. He worked in the Randolph S. Rothschild Collection and the Robert Hall Lewis Collection, both in D.C., as well as the Peabody Archives in Baltimore.

Professor Katz believes the practical skills the fellows learn over the summer are vital to both academic and career development. The initial funds for these fellowships were generously provided by James W. Pruett, who served as chair of Carolina's Music Department from 1976 to 1986 and was Chief of the Music Division at the Library of Congress from 1987 to 1994. Substantial funds were raised by the Music Department under the leadership of Professor and former Chair Tim Carter, Professor and current Chair Terry Rhodes, and Professor Mark Katz. The Graduate School, the Vice Chancellor for Research and Economic Development, and the College of Arts and Sciences also contributed to supporting these students. However, these funds are almost exhausted. Both the Library and future Musicology students could miss out on this mutually beneficial relationship.

Katz states that every time he talks to colleagues at the Library, "they go out of their way to rave about our students and their energy. They beg us to keep the program going, and they want to do whatever they can to make it happen, but lack the resources."

The Library would lose the manpower and specialized musical knowledge that Carolina students provide. The students would miss out on the behind-the-scenes access to the incredible depth and breadth of the Library's collection that reignites their passion for studying music and helps them learn how to conduct archival research.

"It is very clear that there is little money left to continue the program," Katz worries. He hopes this program can continue and both the Library of Congress and future students from Carolina can have the same summer opportunities as their peers before them.

♦ Rebecca Prettyman